# Tell R to print out some words on screen with the "print" command

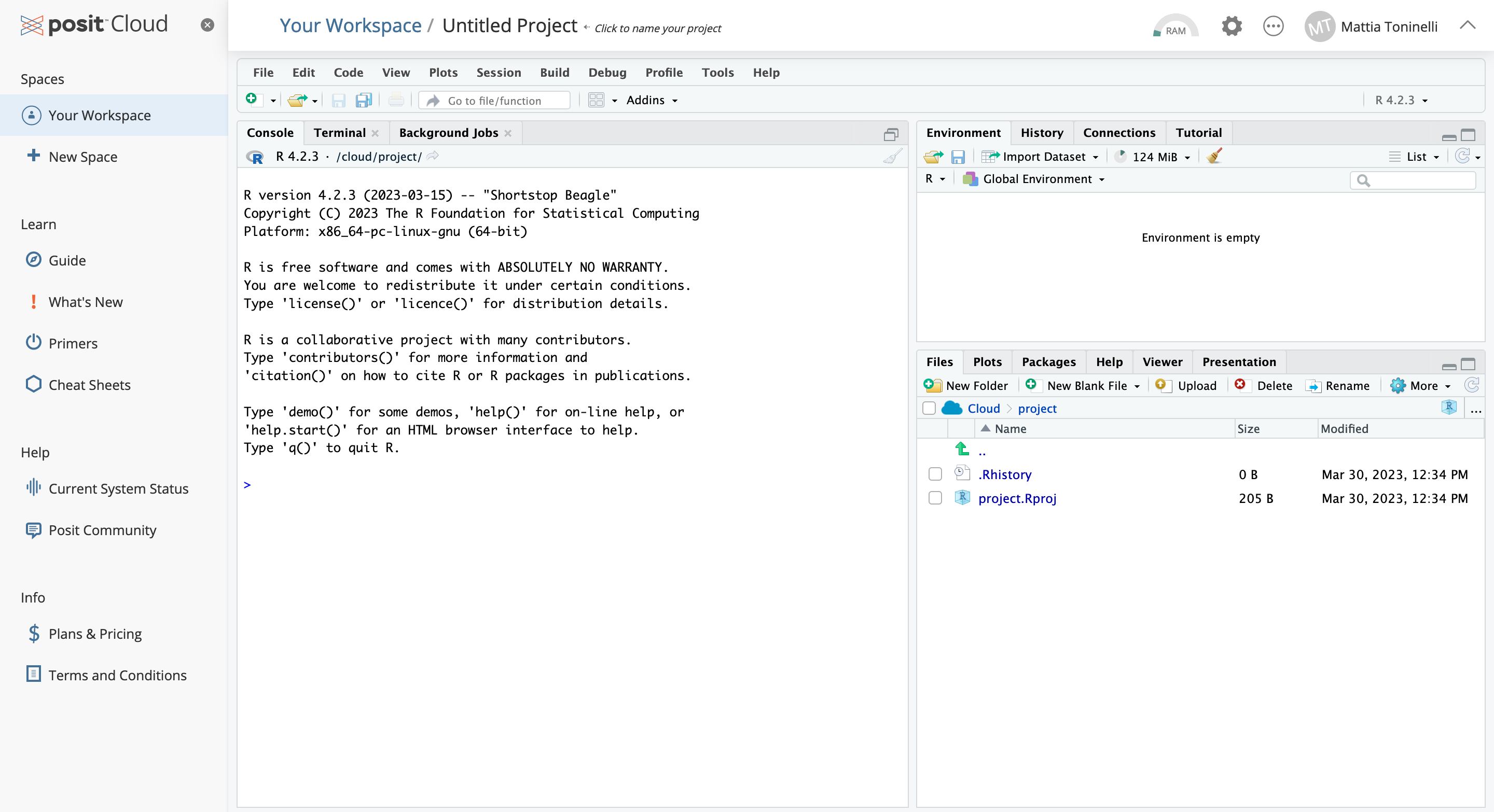

print("Hello World!")[1] "Hello World!"If RStudio is not installed on your computer, you can create a free account on posit.cloud. Create the account with your credentials and follow the instructions to create a new project. Once done, you should see something like this on your screen:

This is your working interface, the bottom right section shows your current file system (on the cloud) which is now pointed to the place where the Rproject you just created lives. The section on the left currently displays your console, where you can type R code interactively.

You should see your cursor on the left-hand side of the screen blinking. That window represents the R console. It can be used to “talk” with R through commands that it can understand!

For example, try typing the following in the console and check what comes out (a.k.a. the output):

One of the main aspects of any programming language including R is the ability to create variables. You can think of variables as ways to store objects under any given name. Let’s take the previous example and store the Hello World! character (known as a string) in a variable that we call my_variable. The creation of a variable in R is classically done through the assignment operator <-.

# Let's assign the statement to a variable (nothing happens when running this code)

my_variable <- "Hello World!"

# Let's display the content of the new variable!

print(my_variable)[1] "Hello World!"💡 What happened in the top right part of your screen when you ran the code lines above? Check out the “environment” section, you should see that

my_variableappeared there!

Without going too much into the details of all the available objects used to store data in R, one of the most abundantly used is the data.frame. Think of data.frames as the R equivalent of Excel spreadsheets, so a way to store tabular data. As we will see later, pretty much all the data we are going to handle will be in the form of a data.frame or some of its other variations.

# Let's create and display a data frame (a table) with four rows and two columns

data.frame("Class"=c("a","b","c","d"), # First column

"Quantity"=c(1,10,4,6)) # Second column Class Quantity

1 a 1

2 b 10

3 c 4

4 d 6You have now instructed R to do something for you! We will ask it to do plenty more in the code chunks below!

In the console we can type as many commands as we want and execute them sequentially. Nevertheless, commands typed in the console are lost the moment they are executed and if we want to execute them again we need to type everything back in the console… this is painful!

A script is just a normal text file which groups a series of commands that R can execute sequentially, reading the file line-by-line. This is much better because we can then edit the file and save the changes!

Follow the movie below to create an R script in Posit, the same applies to Rstudio, notice the .R extension at the end of the file name.

The new window that appeared on the upper left represents your R script. In here we can write R code which DOES NOT get executed immediately like in the console before.

💡 In order to execute code from the script, highlight the code line you want to execute (or put your cursor line on it) and press ⌘+Enter on Mac or Ctrl+Enter on Windows.

The analyses that we are going to conduct require specific packages. In R, packages are collections of functions which help us perform standardized workflows. In the code chunk below, we instruct R to install the packages that we will need later on throughout the workshop.

💡 Copy and paste this and the other code chunks from here to your R script to follow.

# Install packages from Bioconductor

if (!require("BiocManager", quietly = TRUE))

install.packages("BiocManager")

# Install packages from CRAN

install.packages("tidyr")

install.packages("dplyr")

install.packages("googledrive")

# For differential expression

BiocManager::install("vsn")

BiocManager::install("edgeR")

install.packages("statmod")

# For visualizations

install.packages("hexbin")

install.packages("pheatmap")

install.packages("RColorBrewer")

install.packages("ggrepel")

# For conversion between gene IDs

BiocManager::install("org.Hs.eg.db")

# For downstream analyses

install.packages("msigdbr")

BiocManager::install("fgsea")

BiocManager::install("clusterProfiler")

# Remove garbage

gc()During the installation, you will see many messages being displayed on your R console, don’t pay too much attention to them unless they are red and specify an error!

If you encounter any of these messages during installation, follow this procedure here:

# R asks for package updates, answer "n" and type enter

# Question displayed:

Update all/some/none? [a/s/n]:

# Answer to type:

n

# R asks for installation from binary source, answer "no" and type enter

# Question displayed:

Do you want to install from sources the packages which need compilation? (Yes/no/cancel)

# Answer to type:

noHopefully all packages were correctly installed and now we can dive a bit deeper into the theoretical basics of RNA sequencing!

With bulk RNA sequencing technologies, the goal is to capture average gene expression levels across pooled cell populations of interest. This is achieved by capturing all RNA transcripts from a sample and sequencing them in an automated way to ensure the adequate throughput needed for answering the biological hypotheses behind the experiment.

A bulk RNA-seq experiment is articulated in the following steps:

Experimental design: sample choice and hypothesis

RNA extraction

cDNA preparation: retrotranscription of RNA molecules

Library preparation: fragmentation of cDNA molecules and ligation of adapters

Sequencing

Data processing: raw read QC

Data analysis: extract meaningful biological insights

Next Generation Sequencing technologies (Illumina/PacBio) allow experimenters to capture the entire genetic information in a sample in a completely unsupervised manner. The process works with an approach called sequencing-by-synthesis or SBS for short.

💡 Great info can be found at the Illumina Knowledge page

This means that strands are sequenced by re-building them using the natural complementarity principle of DNA with fluorescently labelled bases which get detected and decoded into sequences. On illumina flow-cells this process happens in clusters, to allow for proper signal amplification and detection, as shown in the movie below.

The raw output of any sequencing run consists of a series of sequences (called reads). These sequences can have varying length based on the run parameters set on the sequencing platform. Nevertheless, they are made available for humans to read under a standardized file format known as FASTQ. This is the universally accepted format used to encode sequences after sequencing. An example of real FASTQ file with only two reads is provided below.

FASTQ files are an intermediate file in the analysis and are used to assess quality metrics for any given sequence. The quality of each base call is encoded in the line after the + following the standard Phred score system.

💡 Since we now have an initial metric for each sequence, it is mandatory to conduct some standard quality control evaluation of our sequences to eventually spot technical defects in the sequencing run early on in the analysis.

Computational tools like FastQC aid with the visual inspection of per-sample quality metrics from NGS experiments. Some of the QC metrics of interest to consider include the ones listed below, on the left are optimal metric profiles while on the right are sub-optimal ones:

Per-base Sequence Quality  This uses box plots to highlight the per-base quality along all reads in the sequencing experiment, we can notice a physiological drop in quality towards the end part of the read.

This uses box plots to highlight the per-base quality along all reads in the sequencing experiment, we can notice a physiological drop in quality towards the end part of the read.

Per-sequence Quality Scores  Here we are plotting the distribution of Phred scores across all identified sequences, we can see that the high quality experiment (left) has a peak at higher Phred scores values (34-38).

Here we are plotting the distribution of Phred scores across all identified sequences, we can see that the high quality experiment (left) has a peak at higher Phred scores values (34-38).

Per-base Sequence Content  Here we check the sequence (read) base content, in a normal scenario we do not expect any dramatic variation across the full length of the read since we should see a quasi-balanced distribution of bases.

Here we check the sequence (read) base content, in a normal scenario we do not expect any dramatic variation across the full length of the read since we should see a quasi-balanced distribution of bases.

Per-sequence GC Content  GC-content referes to the degree at which guanosine and cytosine are present within a sequence, in NGS experiments which also include PCR amplification this aspect is crucial to check since GC-poor sequences may be enriched due to their easier amplification bias. In a normal random library we would expect this to have a bell-shaped distribution such as the one on the left.

GC-content referes to the degree at which guanosine and cytosine are present within a sequence, in NGS experiments which also include PCR amplification this aspect is crucial to check since GC-poor sequences may be enriched due to their easier amplification bias. In a normal random library we would expect this to have a bell-shaped distribution such as the one on the left.

Sequence Duplication Levels  This plot shows the degree of sequence duplication levels. In a normal library (left) we expect to have low levels of duplication which can be a positive indicator of high sequencing coverage.

This plot shows the degree of sequence duplication levels. In a normal library (left) we expect to have low levels of duplication which can be a positive indicator of high sequencing coverage.

Adapter Content  In NGS experiments we use adapters to create a library. Sometimes these can get sequenced accidentally and end up being part of a read. This phenomenon can be spotted here and corrected later using a computational approach called adapter trimming, visible in next section’s figure.

In NGS experiments we use adapters to create a library. Sometimes these can get sequenced accidentally and end up being part of a read. This phenomenon can be spotted here and corrected later using a computational approach called adapter trimming, visible in next section’s figure.

Once we are satisfied with the quality of our pool of sequences, we need to map them back to the transcripts to which they belonged originally when we produced cDNA molecules from RNA. This process of mapping is needed to understand from which genes were transcripts generated and therefore is an essential and very important step of data processing!

Alignment of trimmed reads to a reference genome or transcriptome.

Tools like STAR and BWA-MEM are designed to achieve great speed and accuracy for the computationally expensive task of read alignment.

The results of the alignment procedure is a different set of files in SAM (Standard Alignment Map) format which get compressed into their binary representation, BAM files. These are usually one for each analyzed sample and encode the position of all the identified reads along the genome as well as alignment quality metrics for QC, which can be carried out with tools like MultiQC.

💡 All of these pre-processing steps, which are computationally expensive, are usually integrated in pipelines which connect inputs and outputs of these difference procedures in a streamlined manner. An example is the RNA-seq pipeline provided by the nf-core community.

After sequences have been aligned to their respective place on the genome, it is time to actually count how many times a given sequence is found on any given gene (or transcripts, or exons or others..), this will actually be our gene expression measurement!

There are many ways to achieve this task but among the most used is the featureCounts tool. In the end, for every sample, we will end up with a number for each gene (or transcripts), these are called gene (transcript) counts.

These are usually summarized in a table, called gene expression table, where each sample is a column and each row a different gene. We will now load one and take a closer look, this will be our starting point in the hands-on analysis of bulk RNA-seq data.

💡 What is the difference between a gene and a transcript?

We will load a table of data from this study on tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T-cells. The original data supporting the findings of the study has been deposited on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data portal under accession number GSE120575. This is the place where all studies publish the processed sequencing data from their analysis in order for other researchers to download it and reproduce their findings or test their own hypotheses.

We have already downloaded the data and inserted it in a Google Drive folder organizing it as follows:

raw_counts.csv: the gene by sample matrix containing the number of times each gene is detected in each sample (our gene expression values)

samples_info.csv: the table containing samples information, known as metadata, which tells us about the biological meaning of each sample

Open the folder through your Google Drive (this step is important), check the presence of the files in the browser and then only AFTER having done this, run the code below. After having opened the Google Drive folder, follow the code chunk below where we are going to load the data and create two new variables in our R session, one for each table.

🚨 NOTE: After you run the code below, look into your

Rconsole and check if you are prompted to insert your Google account information. Do so and then follow the instructions to connect to your Google account in order to download the data from the shared MOBW2023 folder!

# Load installed packages with the "library()" function

library("dplyr")

library("googledrive")

# Load files

files <- drive_ls(path="MOBW2023")

# File paths with URL

counts <- files[files$name == "raw_counts.csv",] %>% drive_read_string() %>% read.csv(text = .) %>% as.data.frame()

rownames(counts) <- counts$X

counts$X <- NULL

samples <- files[files$name == "samples_info.csv",] %>% drive_read_string() %>% read.csv(text = .) %>% as.data.frame()

rownames(samples) <- samples$X

samples <- samples[,c("Donor","SampleGroup","sex")]We can now explore the data that we have just loaded in the current R session to familiarize with it.

| BSSE_QGF_204446 | BSSE_QGF_204447 | BSSE_QGF_204448 | BSSE_QGF_204449 | BSSE_QGF_204450 | BSSE_QGF_204451 | BSSE_QGF_204452 | BSSE_QGF_204453 | BSSE_QGF_204458 | BSSE_QGF_204459 | BSSE_QGF_204460 | BSSE_QGF_204461 | BSSE_QGF_204462 | BSSE_QGF_204463 | BSSE_QGF_204464 | BSSE_QGF_204465 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENSG00000228572 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000182378 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000226179 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000281849 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000280767 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000185960 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LRG_710 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000237531 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000198223 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ENSG00000265658 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

We can then check the shape of our counts table (i.e. how many different transcripts we are detecting and how many different samples?)

We can see that our table contains count information for 62854 genes and 16 samples.

💡 In R, these table object are called

data.frames,tibblesare just like them but with some improved functionalities provided by thetidyverselibrary.

We can also inspect the metadata from the samples which is stored in the samples variable we created above.

| Donor | SampleGroup | sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSSE_QGF_204446 | HD276 | Trest | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204447 | HD276 | Ttumor | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204448 | HD276 | Teff | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204449 | HD276 | Tex | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204450 | HD280 | Trest | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204451 | HD280 | Ttumor | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204452 | HD280 | Teff | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204453 | HD280 | Tex | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204458 | HD286 | Trest | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204459 | HD286 | Ttumor | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204460 | HD286 | Teff | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204461 | HD286 | Tex | Male |

| BSSE_QGF_204462 | HD287 | Trest | Female |

| BSSE_QGF_204463 | HD287 | Ttumor | Female |

| BSSE_QGF_204464 | HD287 | Teff | Female |

| BSSE_QGF_204465 | HD287 | Tex | Female |

In this case, this samples table has as many rows (16) as there are samples (which in turn is equal to the number of columns in the counts table), with columns containing different types of information related to each of the samples in the analysis.

Let’s save this object with samples information in a file on this cloud session, this might be needed later if we end up in some trouble with the R session! This is a file format where columns are separated by commas. You might be familiar with this format if you have worked quite a bit in Excel. In R, we can save tabular data with the write.table() function specifying the location (the file name) we want. This is useful in the case our R session dies or we decide to interrupt it. In this case we will not have to run the whole analysis from the beginning and we can just source the file and load it!

We can load the object back into the current session by using the following code line:

💡 We will also repeat this procedure with the results of the differential expression analysis in order to avoid repeating work we have already done in case of any trouble!

Now that we have our objects correctly loaded, we can dive into the actual RNA-seq analysis.